I know we all have a "type" of writing we do. We either suffer through multiple outlines, characterizations, photos of characters etc. or we do all this by the seat of our pantser pants.

Here is a dandy article from NOW NOVELS, a site I discovered on Facebook.

Common writing challenges (and how to solve them)

Are you a plotter or pantser? Pantsers write without planning while plotters prepare beforehand with extensive outlines. Both types of writing have their uses. Yet not having a plan sometimes creates problems. Here are common pantser writing challenges we’ve found coaching authors (and ways to get past them):

Common writing challenges (and how to solve them)

Are you a plotter or pantser? Pantsers write without planning while plotters prepare beforehand with extensive outlines. Both types of writing have their uses. Yet not having a plan sometimes creates problems. Here are common pantser writing challenges we’ve found coaching authors (and ways to get past them):

Most common pantser writing challenges

1. Getting writer’s block while drafting

The word pantser comes from the saying to do something “by the seat of your pants”, meaning with little preparation. If you’re a pantser, you most likely find working out plots ahead of time uninspiring, even demotivating.

However, if you go the pantser route, you run the risk of getting writer’s block. Sometimes this is because you write yourself into a corner and don’t see other possible story paths. Other times, you get bogged down in a specific section of your book and lose narrative drive.

If you get stuck with writer’s block while drafting, backtrack to simplified outlining. Think of it like a hawk that’s been hunting between trees and lost track of its quarry. At this level of closeness to your story (the quarry), it’s not always easy to see and choose the best paths for your story development.

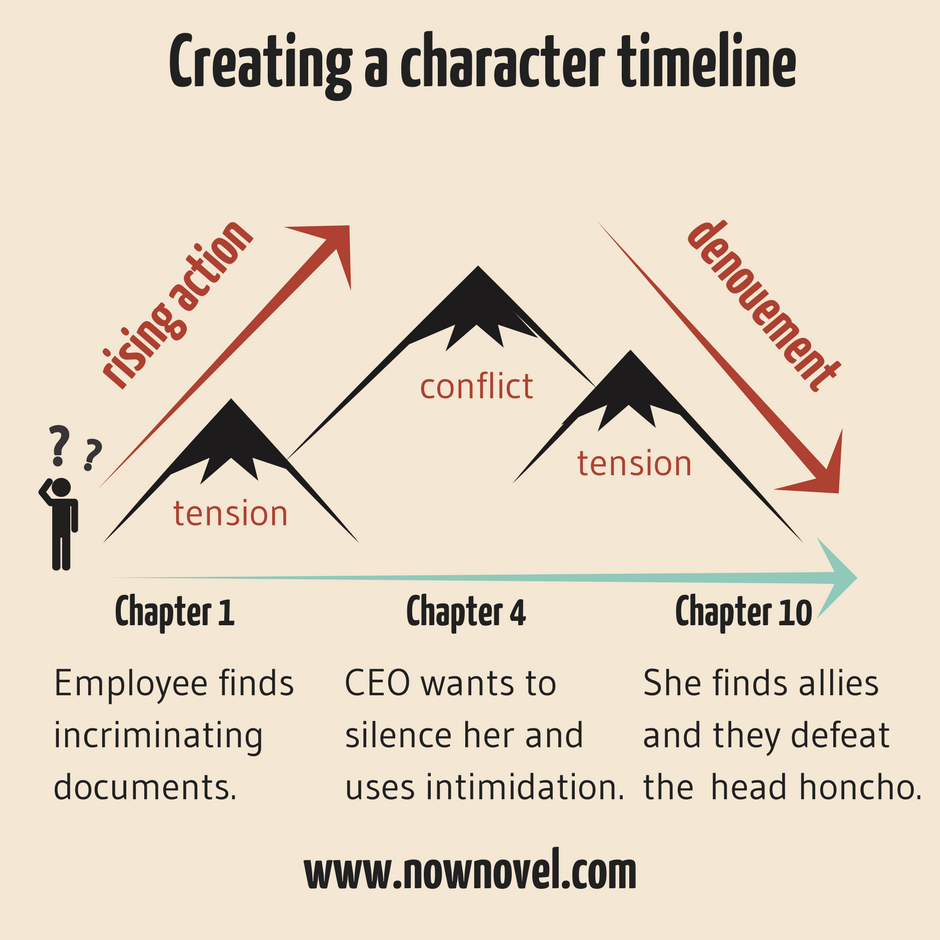

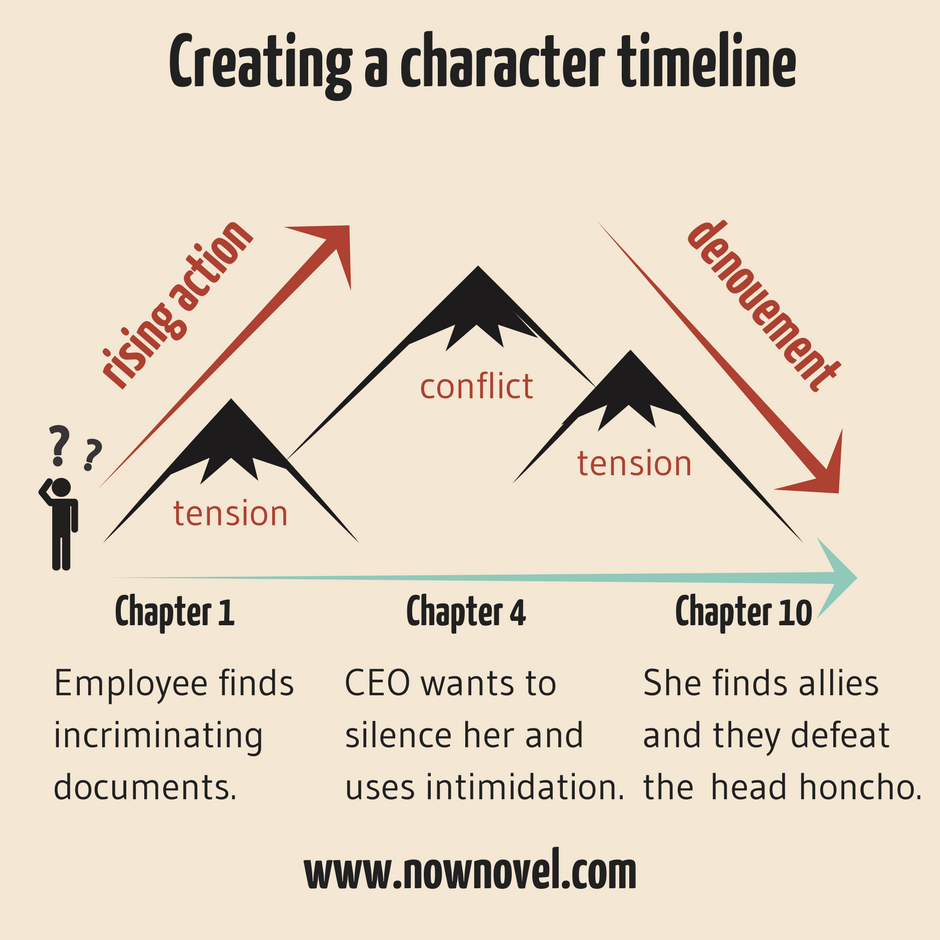

The important thing is to return to a bird’s eye (outlining) approach that works for you. You could create visual timelines of characters’ story arcs, like this:

If you have a condensed timeline like the one above you can start filling in the gaps by asking questions. For example, ‘How does the whistleblower find allies between Chapters 4 and 10? What’s happening in the primary conflict between her and the CEO during this time?’

You can also use the step-by-step Idea Finder on Now Novel to brainstorm ideas and build a story blueprint when you’ve hit a wall using the pantsing approach.

2. Using a flawed writing process

Few writers sit down with no prep at all in front of a blank page and begin writing a story.

Although a lucky few manage to prepare in their heads, most of us make at least some notes. Formalizing whatever your process is to an extent will help you create a repeatable approach that works for you.

Do you begin with a theme, a character, a situation, a setting or something else? Figure out what moves you to begin telling a story (as well as what you need in place to be motivated to continue).

It might be as simple as having someone to hold you accountable to your goals and provide encouraging, constructive input whenever something is holding you back (these are things Now Novel’s writing coaches do).

3. Being too focused on detail

Detail in fiction is important – it helps to make your writing descriptive and immersive. Yet pantsers sometimes get lost in the details. It’s important to be able to keep a macro view of where your story’s heading.

This is another situation where simplified outlining comes to the rescue.

There are many ways to do an outline. Some writers find it helpful to write a synopsis ahead of time.

However, this outlining may be too specific for pantsers in the early, idea-finding stages.

If you need a more general preparatory process, try writing about your novel in the form of interviews with your characters, journal entries by your characters or even a fake book review of your finished novel.

Experimenting with various ways of telling the broad sweep of your story will help you refocus on the larger picture.

Whenever you do create macro structure to guide you, remember this: You have no obligation to stick to it. Think of any outline as a flexible story recipe that you can alter to your personal needs as you go.

4. Losing narrative cohesion

A danger of pantsing is that if you tell the story in one long act of improvisation, it could lose narrative cohesion (the way the pieces of your story fit together). To avoid this, think in story arcs.

Plot arcs are event-driven. They tell the cause and effect, sequence and development, of the ‘what’ in your story. ‘What happens in the first scene? How does this develop in the second scene? What tensions or conflicts result?’ These are ‘what’ questions and picturing them along an arc of cause and effect will help you create a better plot arc, whether plotting them out in detail or as a quick sketch.

Character arcs are also important for narrative cohesion. After all, if a character wants to rule the world in chapter 1 but hates the spotlight by chapter 7, the reader will wonder what brought about this change if you haven’t made it clear via scenes showing cause and effect.

As a pantser, you may prefer one or the other type of arc. Keep in mind that whichever type of arc you sketch out, you should focus on the main points of the story. If you’re working on your plot (event) arc, ask:

If you’re building narrative cohesion by focusing on character arcs, ask:

5. Lacking guiding story structure

Problems that affect pantsers often involve process rather than story. It’s possible to find a happy balance between a structured and a free approach. For example, you can work with a loose version of ‘three act structure’, a type of story structure borrowed from stage plays:

A simplified version of three-act structure for pantsers

Act One: The first quarter of the book, so in a 100,000 word novel, it will be roughly the first 25,000 words.

In Act One, you need to set up the characters and background. Note down ideas for an inciting incident – the even that first draws your main character into the story. Typically, this will end on a turning point or a point of no return for the character by the close of the first quarter.

Act Two: This is the middle section of around 50,000 words.

In Act Two, there is rising action as your character attempts to solve their challenges from act one and the situation worsens. Tension can rise and fall in different places, but there should be a net (average) rise throughout this section as further complications challenge your protagonist. Like act one, this section should end on another major plot point.

Act Three: Roughly 25,000 words.

In Act Three in three act structure, the final action of your story will build to a climax and then a resolution.

There are many variations on the three-act structure including the hero’s journey. By using a few key points from this structure, you can ensure that your novel stays on track as you write it.

Are you struggling to make headway in your novel? Join Now novel for helpful brainstorming tools, an online critique community, and optional assistance from your own personal writing coach.

No comments:

Post a Comment